Editor's Choice

Out of the mouths of babes

Out of the mouths of babes

Sophie Heath

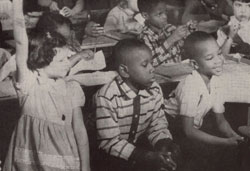

Whilst the census data and Institute speeches available in Race Relations in America offer the opportunity to study the top-level experiences of non-white Americans, the true significance of segregation and discrimination becomes apparent in the detailed interviews carried out by the Race Relations Department fieldworkers. One study in particular has the ability to inform, shock and inspire in equal measures: the parent and pupil interviews that formed part of the Chattanooga desegregation survey.

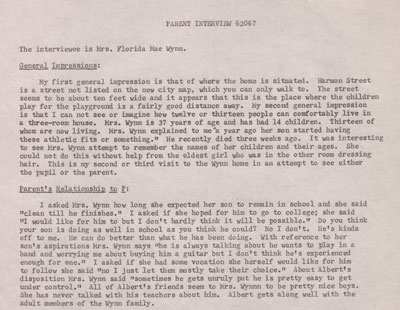

In 1960 fieldworkers visited the families of children whose schools were due to be desegregated, both African American and white. The responses reveal family life in Tennessee, living conditions, attitudes to education, life goals, beliefs and values. Each was also asked for comments on 'racial problems', including recreational facilities, sit-in demonstrations and desegregation of the schools.

It is possible to compare the influence of parents on their children in the perpetuation of prejudice. One parent stated that 'this old world is going to hell and will have a war if it is integrated', and their child repeated this phrase in his own interview. Another child commented that 'most parents have turned young people against the Negroes rather than teenagers themselves', whilst some thought that parents should keep out of the discussion and let children sort it out amongst themselves. Some were taught to accept the situation, with one child agreeing to the question 'Do your parents say that you can’t do some things you want to do because you are a Negro?' and adding, 'Yes, and it’s easy to see because you can find out that the Negro is not free'.

Housing and living conditions were frequently mentioned, indicating number of rooms, cleanliness, household chores, and whether the children had time or space to study. Many children shared bedrooms; one is noted to share 'a room and a bed with three of his brothers'. Another family’s home was 'in a run-down neighborhood and conditions inside the house [were] extremely crowded'. The educational history of the parents was also included, often with comments to indicate whether they wished their child to have the same or different opportunities: 'Mrs Johnson did not go as far in school as she wanted to. She assert[ed] that with a family of 13 it was impossible to make it'.

Interviewers included their observations of the family, giving the responses more personality. One child made a particular impression on the fieldworker: 'I have not yet encountered an interviewee yet so jolly and so amusing and so apparently light-hearted. She answered the questions most intelligently and most seriously', whilst another 'regarded TV and found a great deal more pleasure there watching Pop Eye than he did trying to attempt to answer my questions'.

Interviewers included their observations of the family, giving the responses more personality. One child made a particular impression on the fieldworker: 'I have not yet encountered an interviewee yet so jolly and so amusing and so apparently light-hearted. She answered the questions most intelligently and most seriously', whilst another 'regarded TV and found a great deal more pleasure there watching Pop Eye than he did trying to attempt to answer my questions'.

When asked how they felt about desegregation of the schools, several of the children were in favor of the improved opportunities that would offer; some expressed the pragmatic view that they wouldn’t choose it, but they wanted to continue their education regardless; whilst others announced that they would start fights, quit or insist on being moved to a private school. One African American child stated rather poignantly that 'integration is a good idea. We should have the same privileges as other children. I think they should start in the lower grades first. When children get older they can hate more'.

One African American father stated that 'if all schools were integrated in Chattanooga it would be better all around, we need competition'. White parents tended to either be adamant that segregation should be maintained – one declared that he would move the family back to Alabama if necessary – or recommended gradual integration: 'she thought that a colored person on the school board, opening the lunch-counters, and token integration in the first grade would solve the immediate problem of segregation'.

These interviews allow researchers to interrogate the misconceptions and prejudices voiced by members of both African American and white families, revealing fears about employment, poverty, housing, increased African American voting, and intermarriage. The influences of society and family life are reflected in the words of the younger generation.

'Neither Free Nor Equal'

In the mid-1940s, Fisk University’s Race Relations Department (RRD) assisted in performing a ground-breaking community self-survey of the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota. Both cities had garnered significant reputations as hubs of racial and religious discrimination, with anti-Semitism particularly rife. As can be seen in various documents from the survey contained in the Race Relations in America collection, interviews with members of the community and statistical data collection and analysis enabled the team of RRD fieldworkers to examine the extent of these issues for minority groups. Topics such as housing, health and hospitals, social welfare, churches, juvenile delinquency, employment and schools were all investigated. When the survey concluded, the results were made available to the community who rose to address the highlighted issues, attempting to change attitudes and implement new measures to fight prejudice and discrimination.

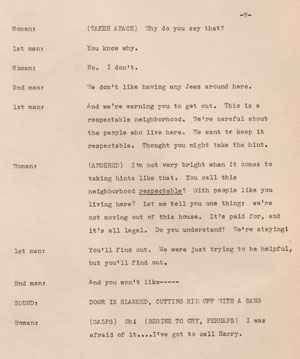

Amongst these methods were a series of radio broadcasts titled 'Neither Free Nor Equal' by WCCO, Columbia’s radio station in Minneapolis-St. Paul, which were aired in 1947. These painted a picture of the extent of the racial and religious discrimination plaguing the Twin Cities, as revealed by the self-survey. Using radio broadcasts to highlight these issues ensured that the everyday social injustices that many people did not see, or chose not to see, were brought to the attention of a wider and more diverse audience. The Race Relations in America collection includes Radio script and excerpts: 'Neither Free nor Equal', radio station WCCO, a script for a 1949 CBS broadcast which, using extracts from the 'Neither Free Nor Equal' series, highlights the community's significant progress made since the self-survey was first conducted. It provides a brilliant example of how such sociological self-evaluations could give communities 'a jolt', forcing them to re-evaluate their own prejudices, fears and actions towards minority groups. It also provides examples of the measures implemented by the community to not only help dispel these attitudes but also to provide support for victims of racial or religious discrimination.

Through short vignettes, the excerpts from 'Neither Free Nor Equal' provide blatant and often shocking examples of everyday racism in the housing and employment sector. An African American woman attending an interview for a book-keeping position at a hotel is told that the 'position is already filled' when she arrives, before being offered a position as a maid. She later calls the hotel using a different voice and name, only to find that the book-keeping position is still available. In another example, a Jewish woman, recently moved to the community, receives a visit from her neighbors who threateningly state 'We don’t like having Jews around here. And we’re warning you to get out. This is a respectable neighborhood. We’re careful about the people who live here.' After the woman shuts the door, the script details the sound effect 'SHOTGUN BLAST AND BREAKING GLASS', followed by the narrator stating '[t]hat happened in a Minneapolis suburb a year and a half ago. The record is in the files of the Minnesota Jewish Council'. Other stories reveal further examples of racial intimidation and discrimination, from children throwing stones at a family who refuse to conform to a neighborhood’s anti-Semitic attitudes, to a Japanese American being refused a job when the interviewer learns that his last name is 'Omata'.

The city’s new measures, put in place to prevent such incidents from recurring, are demonstrated in a number of the vignettes. In a depiction of a landlord who threatens to evict his new tenants due to their association with African Americans, the tenants visit the newly created Minneapolis Mayor’s Council on Human Relations where they are told that the case can be taken to court. Prompted by the St. Paul Council on Human Relations, police lecture a man over his display of a racist sign in his window after discovering that his new neighbors are African American. An employer is visited by a member of the Minneapolis Fair Employment Practice Commission who, following the employer’s refusal to hire a Jewish man, asks 'Are you aware that this city now has a fair employment practice ordinance, and that what you’re doing is against the law?'.

The city’s new measures, put in place to prevent such incidents from recurring, are demonstrated in a number of the vignettes. In a depiction of a landlord who threatens to evict his new tenants due to their association with African Americans, the tenants visit the newly created Minneapolis Mayor’s Council on Human Relations where they are told that the case can be taken to court. Prompted by the St. Paul Council on Human Relations, police lecture a man over his display of a racist sign in his window after discovering that his new neighbors are African American. An employer is visited by a member of the Minneapolis Fair Employment Practice Commission who, following the employer’s refusal to hire a Jewish man, asks 'Are you aware that this city now has a fair employment practice ordinance, and that what you’re doing is against the law?'.

The story of the Minneapolis and St. Paul self-survey was also recorded by journalist Clive Howard in his article 'How Minneapolis Beat the Bigots', providing a means for other communities to discover and engage in the city's struggle towards equality, and offering an equally fascinating read.